If you’ve ever looked outside the terminal windows while waiting for your flight, you might have noticed all the vehicles zipping around moving $100 million dollar aircraft – and it looks like chaos.

*But* there is a method to this madness.

This ramp traffic is constantly driving within close proximity to massive planes, and the drivers need to follow a strict set of rules, and be equipped with special licenses that allows them to operate those vehicles in the first place. It’s a different world inside the boundaries of an airport, and the road system is much different than what you may normally be used to.

So, how does it all work?

To start off, let’s look at the different types of roads inside an airport. I want to mention now that this is based off of Toronto Pearson, so it may vary by airport (but there tends to be a lot of carryover).

Ramp traffic is organised by different categories of roads known as “Vehicle corridors,” which all have a different set of rules. These categories include:

- Service roads

- Outer vehicle corridor

- Connecting corridors

- Tail of stand

- Head of stand

- Terminal service roads

These roads aren’t standard roads like you’d imagine in a city – with shoulders or concrete barriers on the side (or pot holes!). Essentially, they’re all just painted lines on a large slab of tarmac an airport is made out of. I like to imagine this Wall-E scene:

Service Roads

Service roads at Toronto Pearson are all on the outer boundary of the airport, around the fence line. They’re far away from the ‘aircraft movement area’ (any paved areas in the airport planes are able to move on), so vehicles driving on these service roads don’t have anything interesting to see or much to worry about.

Although I said before that these corridors don’t have shoulders or pot holes, this road is the exception. They’re pretty much just regular street roads, with passing allowed, but the speed limit is 50km/h. Unfortunately with all airport speed limits, it’s a strict limit – there’s no going 10 over like on a normal city road (although that’s technically not legal either! Which is why I would never ever speed ever.). 1km/h over this limit is enough to get pulled over.

These roads typically are where the fire stations are, where ramp companies are based, and where airport vehicles can enter the airport through security checkpoints.

Outer vehicle corridor

The outer corridor is still far away from the terminals, but enters the aircraft movement area. This corridor is wedged between the aircraft taxiways and the apron area (area around the terminals). The speed limit on this road is now only 40km/h, and there are frequent stop signs before the road passed over an ‘apron entrance.’ This entrance is where the taxiways meet the apron, so all aircraft travel through this to either take off or get on gate.

Connecting corridors

This one is plural because they’re all over the airport, and they all signify one thing: this stretch of road drives over an aircraft taxiway centreline (AKA, that yellow lines plane follow when taxiing throughout the airport). I bring you the Wall-E example again.

This includes the stretch of road crossing over the apron entrance.

Aircraft ALWAYS have right of way over all other vehicle traffic, and a vehicle must never go across a connecting corridor will even remotely impair the movement of an aircraft. Cutting off aircraft is a understandably big deal, as the pilots are operating off of instructions from the ground control towers, and there may be standing flight attendants that can be severely hurt by sudden hard braking.

If a ground vehicle did cut off an aircraft, the pilots can very easily report it to their company later on and get the perpetrator caught if they’re annoyed enough. That is if one of the thousands of cameras littered throughout the airport didn’t see it already.

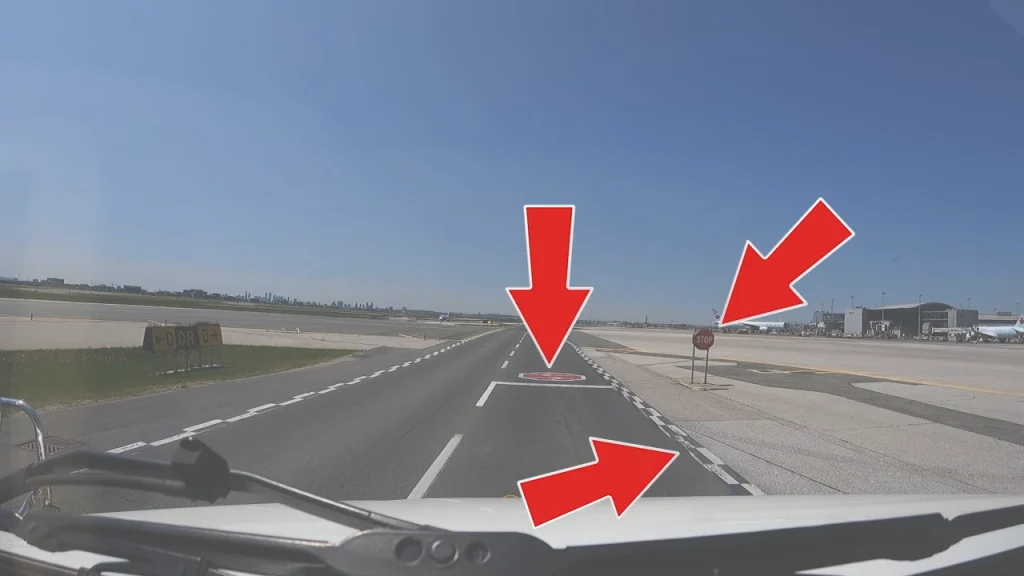

Connecting corridors are marked by these checkered lines, this red sign, and a stop sign:

They are all a giant warning to ground traffic to look out. Everyone needs to slow down before entering a connecting corridor, and ensure:

- Both sides are clear (left, right)

- The place they are driving to (end of the corridor) is clear

Once a vehicle enters a connecting corridor, they have the right of way over other ground vehicles. This means if someone was driving across the connecting corridor from the outer corridor to the tail of stand, traffic on the tail of stand will have to stop and yield.

Right of way of ground traffic is as follows:

- Aircraft

- Emergency equipment

- Airport maintenance performing duties

- All other traffic

Tail of stand

The “tail of stand” is a vehicle corridor trailing behind the tails of aircraft. On this road, vehicles driving around need to start paying attention to aircraft that may want to pull into an empty gate, or live aircraft about to be pushed back. You can almost imagine this as the longest connecting corridor inside the airport, as it follows the entire terminal layout.

Ground vehicles on the tail of stand aren’t using radios to listen for all aircraft getting pushback instructions, instead they need to be vigilant and observe for any indication an aircraft may start pushing back or pulling on to a gate. Pushback, for the record, refers to how an aircraft is pushed by a ‘tug’ (a high torque specialized vehicle) back away from a gate, because these planes can’t move backwards themselves. You can see a demo here:

Signs of an aircraft is about to pushback include:

- No chocks on the aircraft wheels

- The jet bridge is disconnected

- The gate is clear (no vehicles)

- A tug is connected to the aircraft

- There are wingwalkers

- The aircraft’s flashing beacon is on

When you’re driving on this corridor, you’re constantly going through this checklist every time you’re about to pass another gate. Because of this, most vehicles are generously going under the limit of 40km/h as there’s so much to watch out for.

But just as all aircraft need to push back from their gates to begin their flight, they all need to pull onto their gate to kindly dispose of their passengers. There’s really only 2 important signs that an aircraft may pull onto a gate:

- The gate is empty

- There is an aircraft moving towards that gate

There are other signs that suggest an aircraft may pull onto a gate, including:

- Visual guidance system is active

- Marshaller is in position

Ultimately, in this scenario, you should really just be looking over your shoulder to see if an aircraft is coming in. Planes don’t always need a marshaller to pull in. Nor do they even need the visual guidance system – they’re allowed to pull onto and temporarily stop right on the tail of stand whenever the apron control tower tells them to.

Head of stand

The head of stand is on the other, more welcoming side of aircraft – their cute little noses. This corridor is sandwiched between the front of the aircraft and the terminals, and they’re usually where your baggage travels from.

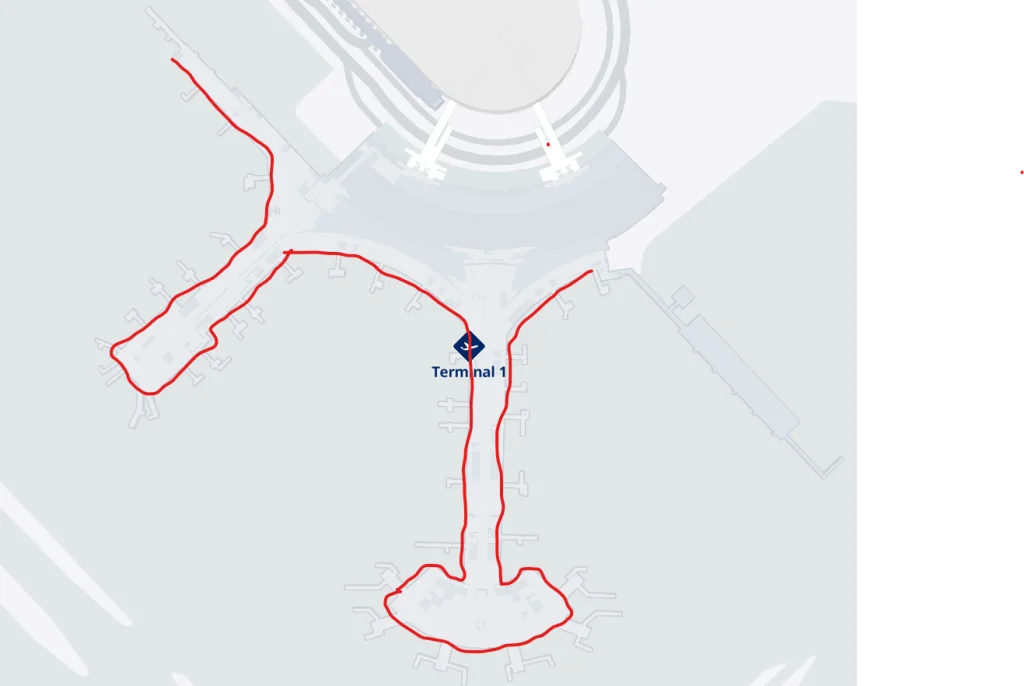

In the picture above, the red line generally marks where this road is found.

They’re loaded with bags from rooms and tunnels underneath the terminal, and then they drive over to their gates. The head of stand is off limit for fuelers and larger vehicles, and the speed limit is a measly 20km/h.

On this road you don’t have to worry about any aircraft movement, but you may have to do some occasional swerving to avoid all the luggages falling off the baggage carts.

Terminal service roads

These roads go directly underneath and through the terminal, and are connected to the head of stand.

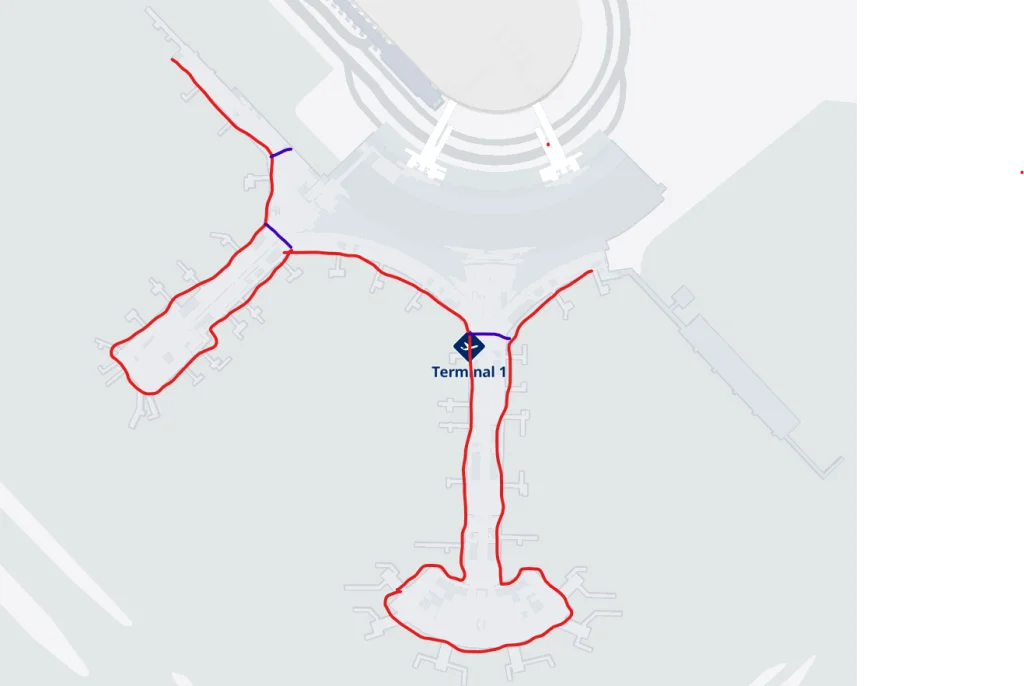

In the picture above, these tunnels are marked in purple. There may be even more than what’s listed above, but these are the major ones.

Some of these tunnels are where bags are brought down by conveyer belts, and loaded onto the baggage carts. Others are really just a shortcut, allowing you to cut directly through the terminal rather than going all the way around the horseshoe.

Just look at Toronto Pearson’s design, and you can easily see how faster that makes things.

The speed limit is only 10km/h here, making it by far the slowest out on the ramp.

Sooo that’s all the roads covered, and it should give you a pretty decent understanding of how airport traffic works. If you want to see a visual representation of this, I have the following video posted:

Otherwise, I’ll add some other tidbits of interesting information…

Low Visibility

When there’s “low visibility operations” like fog, speed limits in the airport are all cut in half. So things get real slow. Airports can’t fully be lit with the giant stadium lights seen on highways, as that’s just going to turn things into an obstacle course for giant aircraft.

They’re mostly lit by pot lights in the ground, easy for pilots to see – but terrible for ground traffic in low visibility conditions. So not only is the speed limit cut justified, but you’re probably going to end up driving even slower than half the limit just to remain cautious.

AVOP Licenses

If you’re studying for your AVOP, and you stumbled upon this article on your search, I at least hope I provided some useful information. I’ll also attach some links for tools you can use, and if you want to check that video I linked just above it may provide some useful real life examples.

If you have no idea what the AVOP is, it’s the license required to drive inside specific areas in the airport. It stands for the Airside Vehicle Operator Permit, and there’s the AVOP-DA permit and AVOP-D permit. The AVOP-DA is the permit required to drive on the designated vehicle corridors, which I discussed all throughout the article. There’s also the AVOP-D, which allows you to drive outside of these corridors and within the aircraft movement area with tower clearance.

Practice quizzes:

Vancouver

https://airsidequiz.ca/yvr/#start

Toronto

https://fellowdrivers.com/avop-practice-quiz/

*Reference your own training materials, and remember it may differ by airport. Don’t rely on these tests completely.