As an aircraft fueler at a busy international airport, if there’s one thing I know in life…. It’s how to fuel planes.

Although this line of work has become so routine for me, I still love to talk to people who don’t work in aviation and ‘stun’ them with elementary information from my job.

Let’s try it on you…

If I asked you “How much fuel can a plane take?”, measured in pounds – what would your best guess be? For reference, a standard car can go from 73-165lbs.

Well, what if I told you the max amount of weight an itty-bitty Boeing 737 can take is 46,000lbs of fuel? Or an A380, fully loaded, can take over 500,000lbs of fuel? No matter what your guess was, that’s simply an absurd number… Especially considering this weight is flying.

When you’re working with such a large volume of fuel, it’s not as simple as pushing in the fuel nozzle and squeezing it until it stops a few minutes later.

With that method, it can take minutes to fuel a 60-100L car, and large flights can very easily take over 100,000 litres (over 300,000 for that A380 example!)

So here’s how it works.

Hydrant System

Large airports almost always utilize hydrant fuel trucks to fill up planes. A hydrant system is where fuel is pumped in underground pipes all throughout the airport, from fuel ‘farms’ outside of the airport boundary (at least in Toronto Pearson).

These fuel farms are where the jet fuel that makes your plane fly is received, filtered, stored and finally pumped throughout the airport and into your plane. It’s where the fuel is constantly and thoroughly tested for contamination, and where the hydrant system throughout the airport is controlled.

These fuel farms usually receive jet fuel by trains, as it’s by far the most efficient method with these vast quantities we’re talking about. Train tracks can run straight through a fuel farm, and nozzles are connected onto the carts quickly sucking it all out.

At the very end of the hydrant system, a hydrant fuel truck drives up to the aircraft, opens up a fuel pit in the ground and then connects to the pit with a hydrant nozzle.

Fuel Tankers

Tankers simply hold the jet fuel within the fueling vehicle itself – no pit connection required. They can get quite large, and ones I’ve driven hold up to 35,000L of jet fuel inside. There are numerous benefits to these over hydrant carts, but a lot of cons.

These tankers are, once again, large. This makes them difficult to maneuver, and aircraft gates can get quite congested. In order for tankers to fuel certain aircraft, the way they need to park may end up blocking ramp agents and catering from accessing the aircraft.

The biggest con has to be the fact that they only hold a limited amount of fuel, opposed to the operationally limitless supply hydrant carts have from the ground. This means if they’re doing very large flights, they’ll have to disconnect from the plane and go to a station to manually fill up the tanker again.

So imagine you’re doing that A380 that requires 300,000 litres with a tanker that can hold no more than 35,000 litres. In that case, you would need to:

- Fill up the tanker 9 times

- Connect to the plane 9 separate times

You see why hydrant carts are almost always preferred? There are some cases in which tankers are actually amazing, which I’ll get back to later.

Fueling the planes

With the help from both vehicles discussed prior, commercial jets receive fuel from pressurised hoses that are capable of pumping 1000-2500L a minute. How fast can a gas station pump again? Like 50L a minute?

I’ll break down the fueling process into steps. Starting with..

1. Dispatching

The airline will determine how much fuel a particular flight needs based on weather, cargo, the route, and amount of passengers. They’ll then send the requested fuel load to the fueling company’s operation room, who will the assign it to a fueler.

2. Fueler positions truck

Every aircraft has a different way that fuelers need to park around it. On a Boeing 737, the fueler will always park on the right side, parallel and in front of the wings. On Boeing 777s, the fueler needs to be guided in by a trained banksman next to the engine on the left side of the aircraft, underneath the wing.

3. Parking brake, turn wheels, chock

It’s absolutely mandatory for fuelers to engage their truck’s parking brake, and then turn their front wheels so they are facing away from the aircraft. This is an extra safety measure so in the event of a brake failure, the vehicle will roll away from the aircraft. Chocks are to be placed around the wheels immediately after the fuel steps out of their truck, which structurally prevents vehicle movement. Next to everything at airports is secured by chocks… Including planes!

4. Connect to hydrant pit

If using a hydrant cart, the fueler will have to connect to the hydrant pit in the ground. Once opening the pit, the first priority should be to place a flag inside of the pit. Fueling trucks include a long, reflective flag to make an open hydrant pit easily visible. The hydrant nozzle is placed onto the pit connection, and then a sensing line is connected to this hydrant nozzle to measure incoming pressure.

5. Electrically bond

Regardless of whether using a hydrant cart or a tanker, the fueler must always bond to the aircraft. There’s a bonding cable located on all fuel trucks, which must be connected to the designating bonding point that all commercial passenger jets have.

The purpose of bonding is to prevent static buildup in the fueling process, as a spark from static electricity is capable of igniting fuel. This is also why fuelers must wear anti-static approved uniforms. It’s a big concern.

There’s been instances at gas stations of this happening to very unfortunate drivers. Maybe this is something you’ve been risking without even realizing it. Using the lock on the fueling nozzle, getting into your car, and getting out to disconnect is how this can really happen. It may sound ‘paranoid,’ but these are real examples that have happened to real people. Here’s a video below showing this effect in action (no injuries):

This isn’t as much of a worry with jet fuel, as jet fuel isn’t quite volatile, but jet fuel is also used in massive quantities and the risk is absolutely not worth it.

6. Connect to aircraft

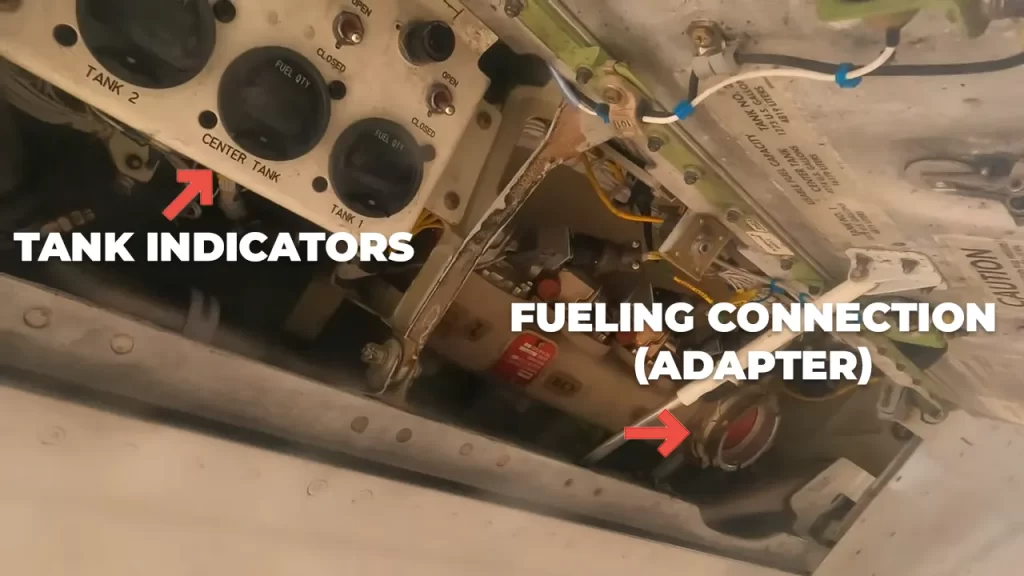

After all of the other steps have been completed, the final one is to connect to the aircraft. With the 737, you need to bring a ladder under the wing, and climb up to open up the fueling panel. Once you do, you’ll see this:

Just simply twist the fueling nozzle onto that fueling connection, and voila!

With the 777, you need to use the lift from your truck to get up to the panel as it’s a much larger aircraft.

The 777 actually has two fueling connections, which is perfect as hydrant trucks conveniently have two fueling nozzles on the lift. This is common for most widebody aircraft. The 777 actually also has another fueling panel on the right side of the aircraft, but that one only has the connections (not the indicators or buttons). This means two fuelers can fuel this plane at the same time, in rare time-sensitive events.

7. Set fuel load (or do manually)

Nearly all commercial aircraft have the ability to take fuel automatically, so the fueler just has to input the requested fuel load from the airline into the fuel panel. The aircraft will balance the weight in the tanks automatically while being fueled, and it’ll shut off before it goes over the requested load.

The 737 is an extremely rare exception to this, and most variations of the 737 need to be fueled manually. Not sure why… But it is what it is. When an aircraft is fueled manually, the fueler has to control the flow of fuel to individual tanks and ensure no imbalances or overfuels.

If the fueler fails to shut off one of the wing tanks before it goes over the maximum fuel capacity of the wing, jet fuel will rapidly start spilling out of the wing vent (remember that 1000-2500L a minute number from before?). If this happens, firefighters need to be called and it can be a huge delay.

8. Start fueling. Observe.

To start fueling, the aircraft fueler has to squeeze a ‘deadman’. This is a device just like the lever you need to hold down on a gas station nozzle, but it’s not directly connected to the fuel hose itself. It’s on a separate cord, allowing the fueler to squeeze the deadman and dance around 40 feet away from the fueling connection if they desired.

Once it’s squeezed, the truck will begin to start pumping. Once released, it will stop the flow of fuel in around 2-5 seconds, as the fuel is flowing so fast it’s impossible to instantly stop it.

Once fueling, the aircraft fueler needs to pay attention to a lot of different things at the same time. They need to be watching the fuel panel to ensure the tanks are balancing themselves, and not going over the weight limit. They need to watch the wings, fuel truck hoses and underneath the truck for any leaks. They’ll need to also watch the pressure gauges on the truck, to ensure the fueling pressure isn’t so high it can damage the aircraft.

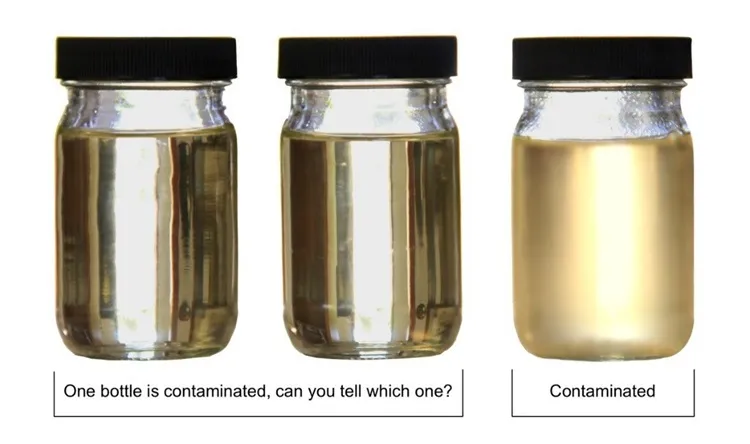

After 1000L of jet fuel is pumped, the fueler will then have to perform a fuel test. There’s a transparent glass jar on the truck, where this fuel can be pumped into and examined. This fuel is taken downstream of the filter, and if any contaminants slipped through the filter it can easily be found after this test. Here’s some examples of what the test looks like:

Water in the fuel shows up as bubbles that would sit on the bottom of the jar, as water is heavier than jet fuel.

9. Deliver fuel ticket

After everything else is done, the fueler records the after fuel quantity on each of the tanks noted on the panel and disconnects from the aircraft. The numbers are loaded into a tablet, which will then print out a ticket that includes some of the following information:

- Before fuel

- After fuel

- Litre uplift

- Time

- Fuel density

The ticket is then brought up into the cockpit and handed to the pilots. Planes usually can’t leave without a fuel ticket, as the uplift information on it is critical. If there’s an issue with the fuel panel not showing the correct amount of fuel onboard, then the plane can run out of fuel before it reaches its destination. So the pilots can mathematically verify this with all the information on the ticket.

If you’re more of a visual learner, I have a full video here showing the POV of an aircraft fueler during this whole process.

Anyways, that’s the standard fueling procedure. There’s also some circumstances where aircraft have to be fueled from over the wing, or even defueled.

Overwing fueling

Overwing fueling almost never happens with commercial jets. It’ll definitely happen with small general aviation aircraft like Cessnas, but the only time a large jet really needs to be fueled in overwing is if it has mechanical issues with its fueling system. Overwing fueling is one of the aforementioned benefits of fuel tankers.

Pressure fueling, the process discussed earlier, requires pushing pressure from the truck and suction from the aircraft. Overwing on the other hand gets the synonym “gravity fueling” as the fuel is simply pushed in by gravity and some light pressure from the tanker. The most common plane to require overwing is by FAR the CRJ, so I’ll be going over the steps for that particular aircraft.

- Fueling tanker positions perpendicular to the wing

- Fueler electrically bonds to aircraft

- A protective rubber mat is placed on top of the wing, next to the overwing fuel cap.

- The fuel cap is taken off, placed on the protective mat – never touching the wing surface.

- The fueling nozzle (in a goosehead variation, seen below) is placed into the fuel adapter. The fueler begins to slowly pump, as another ground worker has to watch the liters from below as it’s out of the fuelers site.

- Only one wing can be fueled at a time using this method, so in order to avoid weight imbalance, the fueler has to switch sides and let the other wing catch up every so often, repeating until the flight is finished.

Defueling

Throughout this article, I’ve repeatedly mentioned specific “requested fuel loads” – and I realize that may confuse some people. I’ve heard several people in my own life question why airplanes aren’t just fueled to their max weight, just like a car? If that question twirls your brain too, well, here’s why:

Airplanes have maximum landing weights.

If a plane has too much fuel on it by the time it reaches its destination, it’s overweight. This can place a lot of stress on parts of the plane, or is downright dangerous as it requires a lot more force to slow down.

More fuel burns quicker.

When an aircraft is heavier than it normally would be, it is less fuel efficient as it requires more thrust to adequately generate lift to support its weight in the air. Adding more than necessary fuel is inefficient as it burns a higher amount of fuel than needed.

Defueling is exclusively done by fuel tankers, and it’s a more complicated process than standard fueling.

Firstly, the tanker has to be fitted into “defueling mode” by a mechanic.

Essentially, the mechanic changes the direction of the filter on the fueling nozzle. Normally the filter traps any potential contaminants from the fuel tanker from getting into the aircraft, but in defueling mode it prevents any potential contaminants from getting into the fuel tanker from the aircraft.

Open the defueling valves

The hookup process is pretty much the same as with good ol’ regular pressure refueling, omitting the hydrant nozzle as it’s a fuel tanker. The unique step with this one is that a defueling valve needs to be opened up on the aircraft. The locations of these vary wildly from aircraft to aircraft. Some aircraft have a separate panel just to open up the defueling valve, like the 737. Or in the 777 you need to reach behind the fueling adapters and pull the lever down on both sides.

Aircraft mechanics turn on boost pumps

Another unique part of defueling is that an aircraft mechanic is required inside the cockpit during this entire process, operating something called ‘boost pumps.’ Fuel tankers aren’t capable of sucking fuel out of an aircraft alone, so these pumps onboard the aircraft can help push it out. They can be used for defueling, and also just shifting the fuel around during flight to keep the tanks balanced.

The boost pumps pump automatically, even if you let go of the deadman. This is actually problematic, as it means if they’re not turned off (which you can’t do yourself) and the tanker reaches its limit, the fuel will spill. Fuelers do have a manual override to pull a lever on the fueling nozzles to stop the flow of fuel, which will prevent this problem from occurring. They then need to speak to the mechanic to turn off the boost pumps, as if they’re on while disconnecting…. Then fuel will still be coming out of the fuel adapters.

Finally, the fuel is tested.

Once the defueling process is complete, the fuel in that tanker must be sampled now for tests at one of the fueling farms. Until they verify that the fuel is clean, that fuel can not be used and the tanker is temporarily out of service.

Once it’s verified, that fuel can be used – but ONLY in the same airline. Air Canada defueled fuel can only be used in Air Canada, for example.

Anyways, thanks for reading. Now you know how airplanes are fueled… *Totally* life changing, huh?